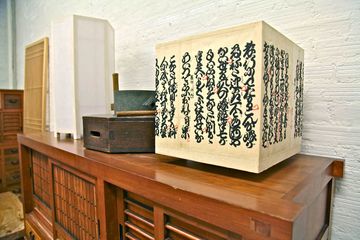

When Miya Shoji opened in 1951, it was not as a house of elegant carpentry. In fact, the company went through many phases - from selling flowers to Japanese knick-knacks - before Hisao Hanafusa eventually guided the business toward wood design. When Hisao arrived in the United States in the 1960s and began working at Miya Shoji, it was owned by another Japanese immigrant, but Hisao eventually made it his own. He had come, "hoping to learn how to miss his home and to see it better from afar." Although he had been a successful painter in Japan, Hisao discovered that he had to start over in NY and, in order to survive, he had to learn many more skills. He began to train himself in carpentry, textiles, and cooking, and he also worked at the Miya Shoji shop, on the side, to pay rent. Hisao had an abundance of stories to share, but it was how his career as an artist in New York began that resonated the most with me. Early on, he was walking down the street and noticed a sign for an art competition—but the submission date was the next day. He raced home, whipped up a painting and mailed it off with the paint still wet. Needless to say he won, and received enough money to continue on in the United States. Hisao went on to tell me that in the late 1960s, he was working in his loft with the door open when someone walked by, smelled the turpentine, and came in to look. He turned out to be an art dealer who wanted to buy Hisao’s painting, but Hisao said that he only wanted to put his paintings in a gallery. The art dealer, unperturbed, simply asked “What gallery?” Hisao, on a whim, named the most prestigious gallery that came first to his mind. Shortly afterwards, his work was featured at that gallery and viewed by Peggy Guggenheim, herself, and, ultimately, a piece of his work was hung in her family's museum. Still, even as a fairly successful painter, supporting his family was difficult and Hisao eventually decided to take over the Miya Shoji company and devote it entirely to the art of Japanese carpentry. He now owns and operates the shop with his son, Zui. The Hanafusa's use only traditional tools and methods to create classic Japanese pieces - shoji (screens used to divide rooms), chests of drawers, tables, and flat bed frames. The style is meant to look as if it came to be naturally, fit together with joints as opposed to hammers and nails. "It is made to last," Zui explained. It is important to father and son that their simply stunning work - which has been featured in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts - be passed down through the generations.