It would be easy to walk right past the East End Temple. From the street, it does not look how one might expect an active synagogue to appear. It is part of a row house designed by the renowned Beaux-Arts architect Richard Morris Hunt for Sidney Webster, a governor of New York, United States senator, and Ulysses S. Grant’s Secretary of State. Its exterior is impeccably well-maintained, and has been designated a New York Historic Landmark. It is the splendid interior, however, on which the congregation has truly left its stamp.

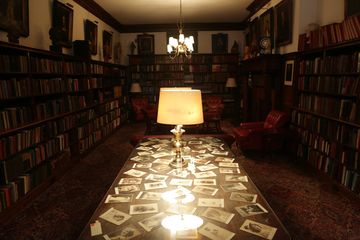

East End Temple was founded as Congregation El Emet (which means “God of Truth” in Hebrew), a name they still use, in 1948. Its founders were World War II veterans living nearby in Stuyvesant Town. For the first part of its existence, the congregation met in a building at 23rd Street and Second Avenue. In 2004, the congregation moved into its current building following a complete architectural overhaul that involved refurbishing and restoring the Helen Spring Library. Original elements from the house’s use as a private residence are plainly visible, and the construction of a brand-new sanctuary received the 2005 American Institute of Architects Honor Award in the category of outstanding interiors. Incidentally, Richard Morris Hunt was a founding member of that very organization.

Lauren Weinberger, a longtime congregant of East End Temple, told me that the congregation had originally planned to build and move into their new sanctuary earlier than 2004. One night in 2001, they had a marathon meeting in which they finalized plans for the new space and hammered out every last detail. That night was September 10. Needless to say, contractors, city permits, and most importantly, emotional stamina and confidence were difficult to come by directly following 9/11. In a sense, the now-completed sanctuary serves as a monument to the refusal of New Yorkers to put their communal and spiritual lives on indefinite hiatus.

The sanctuary, flooded with light from a hidden skylight, appears larger than its actual physical size. Nearly every element of its design is meant to evoke Israel and the Tabernacle. The wall behind the bimah - the raised platform at the front of the sanctuary - is made of Jerusalem stone, with eighteen bronze prayer strips that resemble the paper prayer strips placed by worshipers in the Western Wall. The lectern is made of wood similar to the acacia (now endangered) used in the Biblical construction of the Tabernacle, with hand-holds built into the front to represent "portable nature." Features such as the L-shaped pew arrangement and low bimah make for a community-oriented synagogue experience. The design of the sanctuary was intended to be “non-hierarchical,” Lauren explained. Even the Ner Tamid - the lantern holding the ceremonial eternal light of God - is hung from a long beam extending from the center of the sanctuary, making it seem more accessible.

For me, however, the most striking feature of the sanctuary’s design is the ark doorway made from cast bronze. After hearing of a Buddhist tradition in which prayers are burnt in the crucible where a Temple bell is cast, the congregation decided to adapt the custom for their own Jewish practice. When casting the ark doors, congregants’ prayers were thrown into the crucible and are now part of the doors’ very substance. As for the design of the bronze itself, the doors are meant to feel “tactile,” with linen-like textures and a tree motif representing the Torah, often referred to as the “Tree of Life” in Jewish practice.

The sanctuary reflects the priorities of the congregation it houses. “We pride ourselves on being inclusive and welcoming as a community,” Lauren said proudly. East End Temple is home to a thriving religious school, members of New York’s LGBT community, and to this day, some of the original founders of Congregation El Emet. Some subsets of the congregation even have their own nicknames, like BEET: The Boomers of East End Temple (“a healthy empty-nesters community,” as Lauren describes it). Special events such as summer services in Stuyvesant Square and monthly Simchat Shabbat services, which feature music, comedy, and guest speakers draw healthy numbers of participants. The congregation is active in community organizations like Metro IAF-NY, and enjoys a genial relationship with nearby St. George’s Episcopal Church and Friends Seminary. “The best thing you can do is be a place people want to be at,” Lauren said of her synagogue. “It’s been a wonderful space.”