TJ English knows how to summon the spirits of Midtown’s once intoxicating, infamous jazz scene. The New York-based author, known for his many works examining the sordid underbelly of the American experience (including the seminal Hell’s Kitchen history The Westies) has just released his newest book, Dangerous Rhythms: Jazz and the Underworld.

Author TJ English at Birdland on W44th Street. Photo: Phil O'Brien

In it, he resurrects the souls of the mobsters and musicians — strange bedfellows whose collaboration led to decades of flourishing jazz clubs and whose legacies have faded with the passage of time and an unspoken code of silence.

“It was more fun than any book I've researched or written,” said English. “The fact that I was able to put on Duke Ellington as I was writing about him — to play some of those records live from Birdland in the 1950s, it was more possible to evoke the subject matter than anything else I've written.” He was even inspired to make an accompanying playlist for readers: “I got to walk hand-in-hand with the spirits of Louis Armstrong and all these wonderful characters. When you do this kind of history book, at some point, you merge spiritually with the subject matter and intermingle with the spirits of the history that you're writing about.”

Count Basie in New York in the late 1940s. Photo: William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

English added, “I've been a lover of jazz since I was a teenager. When I first fell in love with the music, I would go to record stores and purchase used vinyl of all the great music from the 1930s and 1940s.

"Part of the process of loving and taking in the music was also a process of educating yourself about the culture and the history of the music — to bring those records home, filled with liner notes and information about the musicians.”

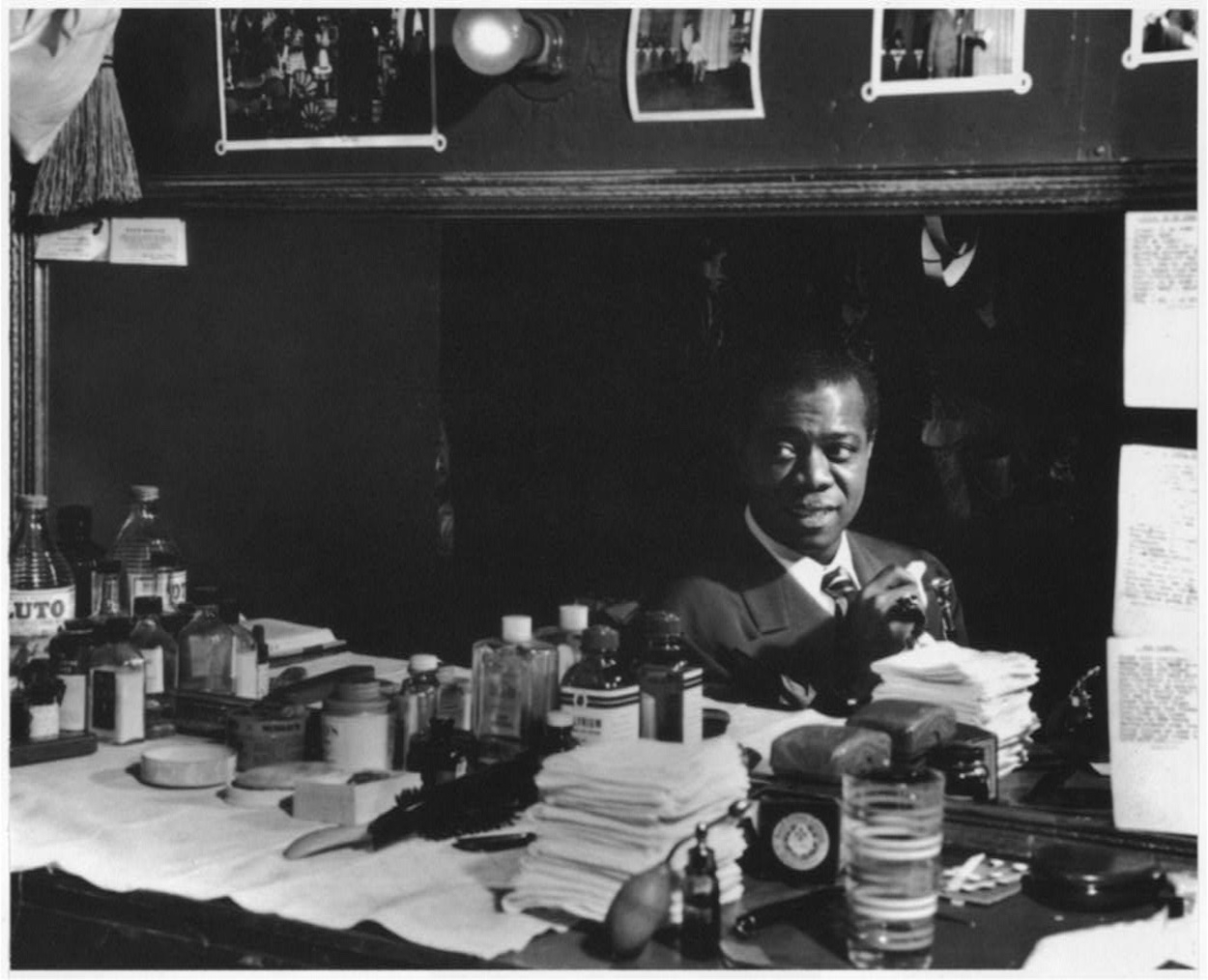

Louis Armstrong in the dressing room at the Aquarium Club on 52nd Street in July 1946. Photo: William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Intrigued by the history, English dove deep into researching his favorite musicians, finding that “many of them made reference to this relationship between the underworld and the musicians that had existed, going all the way back to the beginning of jazz. I was aware of this aspect of the story of jazz and I also was aware that there had to be a lot more to it because for the longest time the musicians didn't talk openly about this. The old-timers like Duke Ellington and Count Basie and Louis Armstrong wrote memoirs later in life where they reflected back on this relationship after the underworld figures were dead and gone,” he said.

Years later and having researched the criminal underbelly of many facets of American life, English decided to look into the unspoken connection between many of his favorite musicians and the mobsters who made their careers. “It was a hidden history for a long time, so it was hard to gather information,” said English. “In fact, I kind of wish somebody had written this book decades ago when some of these musicians were still alive and could have done first hand interviews with them.” To further his research, he explored oral histories recorded by institutions like The Smithsonian, the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University and the memoirs of jazz musicians who outlived their mobster handlers.

For the author, the next challenge was to thread the many stories of mobsters and musicians into a historical through-line, where Louis Armstrong and the mob-run clubs of New Orleans were the key. “You have to go back to New Orleans to get at the roots of this relationship between Sicilians and African Americans and how that was so central to the establishment of the clubs,” English explained. By starting with Armstrong in the (now-defunct) “Storyville” clubs of New Orleans and passing through Chicago, Kansas City, New York and eventually, Las Vegas, “it explains so much about the relationship between African Americans and the Mafia,” he added.

Fats Waller was kidnapped so he could play at Al Capone's birthday party. Photo: Alan Fisher/World Telegram & Sun/Library of Congress

In a world where marginalized communities like Italian, Irish and Jewish immigrants and African Americans created their own, albeit often unevenly distributed, power structures at a time where the White Anglo Saxon Protestant ruled supreme. English dives head first into the alternative social structures particular to the jazz club business model.

“It’s the story of the formation of the underworld in the United States, and it involves the sons and daughters of slaves and the immigrant class,” he said. “The clubs were a reflection of a capitalist structure —and in the United States of America, capitalism in the early 20th century in particular has a racial cast to it. So the owners were white and the labor, in the case of the music, was mostly by African American musicians, and that became the overriding principle.”

Examining an underworld where notorious gangsters would simultaneously protect, promote and torment the Black musicians at their clubs — one story in the book details the time that the infamous Al Capone’s goons kidnapped Fats Waller at gunpoint so that he could play at the mobster’s birthday party — English was curious as to why so many jazz musicians were willing to align themselves with such clearly dangerous public figures.

“I looked at the history leading up to the onset of jazz, and how the underworld and the upper-world were these parallel universes —the upper-world being the White Anglo Saxon Protestant economic and social structure, and then there's this underworld black-market economy of immigrants striving to achieve some version of the American Dream,” he said.

Nightlife on 52nd Street in 1948. Photo: William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

“The way that is all tangled up with violence and race is a big theme that is endlessly fascinating to me,” he added. “It's like taking the blinders off — it sheds a lot of light on a lot of things about the United States’ particular kind of dysfunction, and the way that the United States is wrapped up in violence and racial conflict in ways that we don't even seem to understand a lot of the time, so many of these issues still remain unsolved.”

Taking a close look at the “plantation mentality” of many early jazz clubs — Black employees and musicians serving a segregated patronage in clubs owned by white men, along with disturbing imagery of servitude even present in the decor — English realized that despite the racist power structures inside the clubs, many Black musicians chose to remain involved as an alternative to what was going on outside. “In researching this, what jumps out at you is this 30-year reign of lynching from the time of the Emancipation Proclamation and Reconstruction all the way through the latter part of the 19th century into the 20th century,” said English.

“It started to become clear to me why musicians would be willing and in some cases, more than willing to partner with people who were considered to be violent criminals — the truth is, the average jazz musician had less to fear from a mafioso than he did from a white cracker out on the street or a policeman. Given the way American society was, the clubs that were controlled by the underworld became almost a source of refuge for African Americans. It explained why they would be willing to partake of this sort of relationship — because the alternative was even worse.”

Sarah Vaughan singing in New York in August 1946. Photo: William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

The dynamic would continue on for many of the greatest jazz musicians, from legendary Black jazz performers Sarah Vaughan and Duke Ellington and Count Basie to Italian crooners like Louis Prima and Frank Sinatra, who was widely known for his association with the mob. “Sinatra didn't invent this relationship between the musician and the mobsters,” said English. “He certainly utilized it, probably as much or more than anyone in this history did, but in many ways he was born into it. His relationship with the Mafia was sort of an outgrowth of what had been laid down as the parameters of this relationship going back to the early part of the century, before Frank was even born.”

Sinatra and many of the characters memorialized in English’s book made their way in New York’s jazz clubs, many of them on Manhattan’s West Side. Already a Hell’s Kitchen expert from his time working on The Westies, English noted the connection between the underworld of Hell’s Kitchen and the mobbed-up jazz scene. “So much of Prohibition and activity related to illegal booze was centered on the West Side around Midtown,” he said.

Sinatra and the boys, circa 1988 at the Westchester Premier Theater with mobsters including Paul Castellano (far left), Carlo Gambino (third from right), and Jimmy “the Weasel" Fratianno (second from right). Photo: FBI

“The largest brewery in town, which was owned and run by Owney Madden, was in Chelsea. The warehouses where so much of the illegal product was stored was in the Hell's Kitchen area. There probably were more speakeasies within Hell's Kitchen than anywhere else in the United States,” he added, although there’s no official way to quantify the statistic. “There was so much underworld activity related to the West Side. When I did the book The Westies, I would often walk around the neighborhood and go to the locations and unleash the ghosts of the spirits of this history and get a sense of what was once there.”

When it came to revisiting Midtown’s jazzy past, English had significantly more difficulty — W52nd Street and the surrounding blocks, once the center of the scene and home to legendary venues like the Hotsy Totsy Club and the original Birdland — show no trace of their nightlife legacy, save for a few restaurants on the block that Mayor Eric Adams enjoys frequenting. The Hotsy Totsy Club at 1721 Broadway, site of an infamous triple shooting in 1929, now appears to be a Dunkin’ Donuts. “I went up to 52nd Street for the first time decades ago and there was not a single trace of anything other than the 21 Club — which is now no longer there. That was the only remnant that was left. I mean, not a single building,” he said. “The fact that something that vibrant could be papered over and forgotten, it’s one of those things that makes you feel worthless — If something like that could be born and rise and now there's no trace of it at all, what's going to be left of you? We're all just little specks of sand in the universe if that scene can be papered over completely as if it never existed.”

The scene on 52nd Street looking east from 6th Avenue in July 1948. Photo: William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

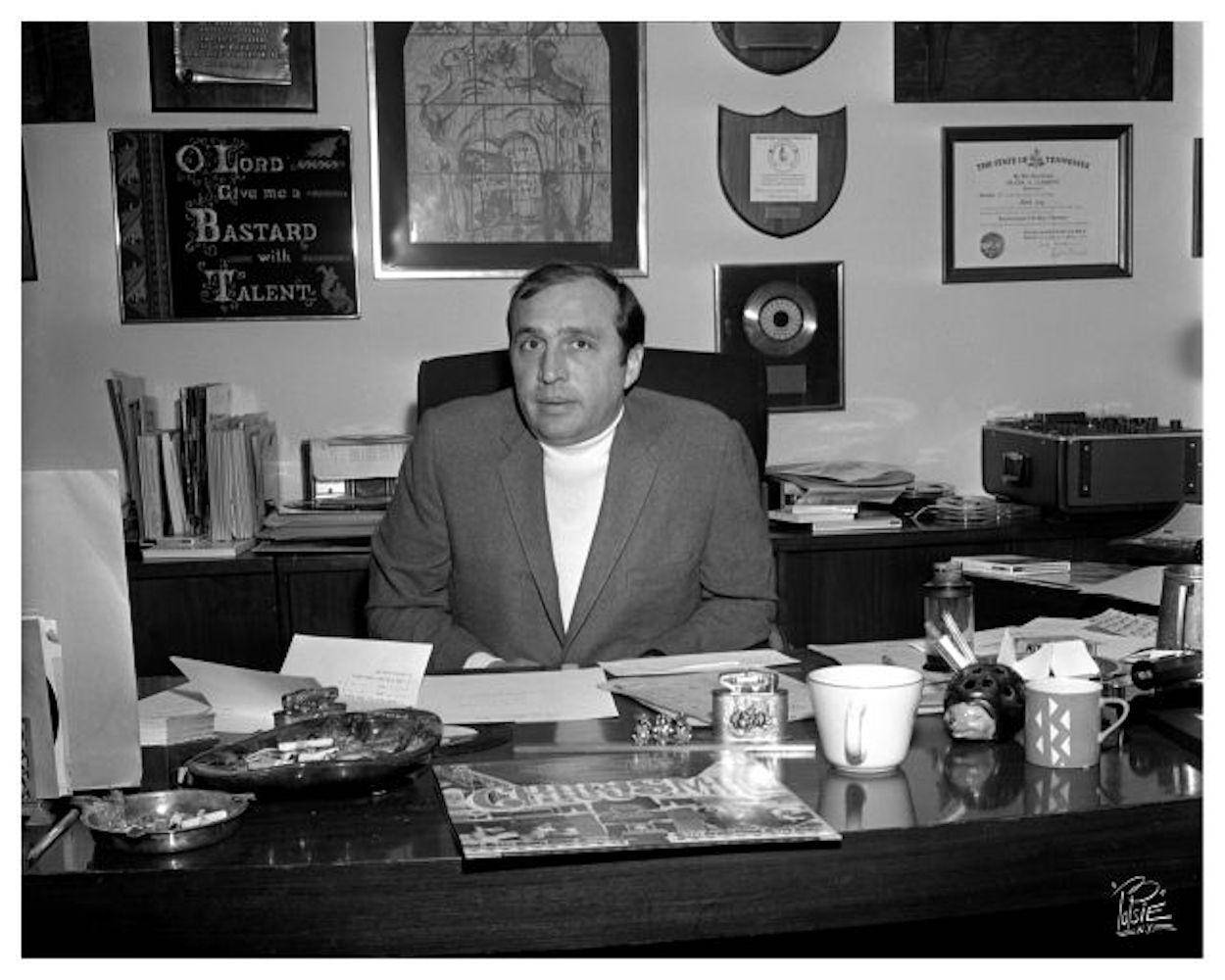

English explored what is left of the past by visiting Midtown’s current iteration of Birdland (after closing in 1965 and briefly opening uptown, the iconic club returned to Hell’s Kitchen and settled on W44th Street). “I cherish the opportunity to go to Birdland, even though it's not in the same location where it was originally,” he said. The club is the setting for a story featuring one of his most cinematic characters — Morris “Mo” Levy, owner and operator of the original Birdland.

A lifelong entrepreneur-turned-criminal, Levy simultaneously managed to promote a more progressive racial environment at his club and cheat many musicians of color out of their fair share of the proceeds. “Mo Levy is an interesting, and in some way, central character to the telling of this tale,” said English.

Morris "Mo" Levy at the offices of Roulette Records. He was a pivotal part of TJ English's story. Photo: Richard Carlin/Wikimedia Commons

“By 1949, segregated clubs were no longer the norm, but they still de facto existed. What distinguishes Birdland was Mo Levy's deep understanding of jazz — I mean, no bones about it, he was a crook and a hoodlum and he proudly took advantage of musicians — he provided them with musical opportunities and then screwed them on the money. But what we appreciate about Levy was his progressive appreciation of the music. What Levy understood as the secret of running a jazz business in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s was that the true aficionados of jazz wanted integrity and authenticity in the music,” added English.

“They didn't want watered down forms of jazz,” or an all-white patronage, he said. “The true jazz fans needed to know that there was a place to go hear the music in its authenticity, not some marginalized version of it and so Birdland became known for that — Birdland became associated with jazz in its purest form.”

Another Midtown legacy venue that gets a mention in Dangerous Rhythms is the infamous Copacabana, then known “not just as mob friendly but as Mafia friendly,” said English. It had a reputation for treating Black performers poorly in its earliest years (Sammy Davis Jr among them), “It's very curious to me, because there was a certain camaraderie to the relationship between the Italian Americans and African Americans in the early part of the 20th Century. They were simpatico to a certain extent with African music and culture. And so Sicilians in the United States sort of naturally formed this relationship with African American musicians,” said English.

“But somewhere along the line, this went off on a different trajectory for Italian Americans, so that by the time you got to the 1960s, the Copacabana becomes kind of self-identified with racism.” Eventually, the power of the civil rights movement broke down the racist power structures at the Copa and made it a more welcoming place — and Sammy Davis Jr even went on to perform headlining sets.

The Copacabana is just one many musical, sometimes mythical stories in Dangerous Rhythms that fascinated English throughout his research. But which ones have stayed with him?

Duke Ellington — "The music that he was creating at The Cotton Club in the late 1920s, to me, is the greatest distillation of the relationship between jazz and the underworld." Photo: Charlotte Brooks/LOOK Magazine/Library of Congress

“To me, Duke Ellington is of God,” said English. “The music that he was creating at The Cotton Club in the late 1920s, to me, is the greatest distillation of the relationship between jazz and the underworld. I think more than any other composer, he was willfully and knowingly creating music that was the fruition of this relationship. I don't think he would've written those songs in the way that he wrote them if it had not been for the fact that here he was playing in a club owned by gangsters in front of an audience of white people who had come to Harlem to sort of slum in Black culture in a sense — he was hyper-aware of all of this as he composed.”

English added: “I also loved having the opportunity to tell the story of Mary Lou Williams in this context. I knew about her as a piano player and an artist, but I didn't really know the full sweep of her career. She pops up in all the jazz eras along the way. I didn't realize how disgusted she became by the whole business.

"To learn her story where she converted to Catholicism and she returns to music to write a mass — it was a relief to have a narrative that ended on a positive note. She was one of the musicians who rose above the underworld.”

Mary Lou Williams at the piano in the CBS studio, New York in April 1947. Photo: William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

English hasn’t given up on the underworld, however, as his next project focuses on another criminal industry — the birth of the cocaine industry in the United States as seen through 1980s Miami in The Last Kilo. “It’s from the point of view of a guy named Willy Falcon and his partner Sal Magluta, who pioneered cocaine, importation and distribution in the United States, starting in the late 1970s all through the 1980 and who created the whole Miami scene.”

Will his next adventure summoning the ghosts’ of Miami’s cocaine-fueled decades take as much research as this deep dive into the underbelly of jazz? “I often start out with an idea thinking, ‘Oh, this is great. I can do a 300-page book, this will be nice and manageable,’” said English. “And then I get into it and I guess I tend to see things in the big picture, in the large context — providing all the research, putting the story in the broadest context possible so that you have what is almost the definitive version of that material of that story. And I always wind up back at the big mountain of research. I wish I wrote short books!”

Birdland in the early 1950s when Ella Fitzgerald was headlining. Photo Public Domain

Dangerous Rhythms: Jazz and the Underworld is available at all good bookstores and on Amazon.

This story originally appeared on W42ST as "TJ English Summons the Ghosts of Midtown's Jazz Scene in "Dangerous Rhythms" in August 2022.