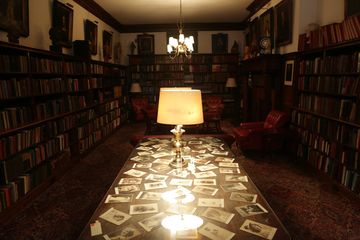

“Most of my dolls I find in the streets. ”Sound is the first thing I notice upon entering Mikel Glass’s new installation on the second floor of The Cell, a performance theater and experimental exhibition space on West 23rd Street. The dense murmur of whirs, whizzes, and running water that comes from mechanical contrivances made of dolls, toys, garbage, and hardwiring gives the impression that I have wandered into a mad tinkerer’s workshop. The dolls gyrate, jump, wave, urinate; in one, a glowing read heart pumps blood through rubber arteries. And that’s to say nothing of the second room of the installation. Glass lurches around the room, shutting off the automatons one by one with crude switches. “I grew up in a small town where if you needed something done, you kind of had to do it yourself, ” he says, a modest explanation for the array of technical skills on display in his installation at The Cell: painting, graphic design, sculpture, carpentry, circuitry. An art-world dissident with decades of academic study behind him, Glass prizes free creativity in contrast to what he sees as a calcified Chelsea art-market machine. As a place for an experiment in what he calls “non-commercialism, ” The Cell is more than a gracious host - for Glass, it is “a little utopian entity on [Chelsea’s] doorstep, in direct opposition to it. ”Having spent decades in the New York art world, he seems only to have gained momentum in the fourth decade of his career, putting on three solo shows in the city in the past eight years, and appearing in a number of other exhibitions around the world. Glass’s easy manner, as well as his choice of materials and relatable themes, conceal to an unsuspecting eye the hours of arduous effort he spends constructing the objects on display. A painted wooden pizza box in one corner of the second room of the installation bears, for example, in faux grease-stain silhouette, a subtle billowy Renaissance head - a reference to Jan Van Eyck’s Portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini, perhaps - and a greasy “Napoleon Crossing the Alps”; On the mantel, a fabricated exhibition catalogue describes bogus art historical lineages of each object in the room, such as the supposed link between a box of aluminum foil and the scene of Kurt Cobain’s death - a falsified link as, in this case, the object is not the original but was, in fact, constructed by Glass. On the surface The Cardboard Project is self-consciously Warholian, even Dadaist, in its commentary on materialism and the art world as a whole, and it is no coincidence that direct references to Warhol feature prominently in this section of the installation. Everything Glass does seems to beg the same response from his audiences: one has to look three times, and then again, to start to construct a personal understanding of the work. It is exactly such individual interrogation and reflection that Glass wishes to encourage with his work. He wants people to think for themselves: “I want people to look at [the work], and then have this reckoning. ”These days, Glass throws himself at his work with as much energy as ever, but as for Chelsea, it seems familiarity has bred increasing contempt. “That whole [Chelsea] gallery experience has become very antiseptic, ” he says, “The edges of the New York art world are starting to get very soft. There used to be a lot of grit, a lot of things you could see and do that were very experimental. With fee structures being the way they are, and […] the general appetite for culture going in the way it is, those places are starting to dry up. The idea of a place dedicated to culture is becoming outdated. The most pure artists who are making the most intrepid work are being pushed out. ”Glass defiantly positions himself, and his work at The Cell, in contrast to the sanitized galleries and mercenary tastemakers. “It’s a fashion show, it’s a popularity contest. Me, I’d rather die in obscurity than compromise, ” he says. Forays into the lucrative curatorial world - namely, a stint at a Basel art fair that he said felt like being “a vegan at a sausage festival” - have convinced Glass of the need to promote the “liberalism and open-mindedness” which he believes to be the highest virtue of art. Along those lines, the installation will feature “expeditors, or emcees, I don’t even know what to call it, ” says Glass, who will both lead guests and reinterpret the experience. Guests are likely in for a wild evening: “We’ve talked to witches and mediums and psychiatrists, and a child and woman who is like a human doll. ” Although the installation will remain largely unchanged over the course of Glass’s residency, the different "expeditors" will offer guests fresh, ephemeral takes on the artwork. Indeed, Glass seems to have entered the most ambitious phase of his career: the exhibit at The Cell will combine his artworks with augmented reality and live performance. Aiming at nothing less than a gesamkunstwerk with this experiment, Glass nonetheless has a sense of humor about the reckless abandon of his endeavors. “An artist is a portal to the zeitgeist, ” he says, then quickly: “Oh my God, that sounds so ridiculous. We’re trying to be as experimental as possible, with the risk of failing. We might fail; I just don’t give a shit. ”