Many New Yorkers recognize Gracie Mansion as the mayor’s residence, but few know that the first floor functions as a museum.

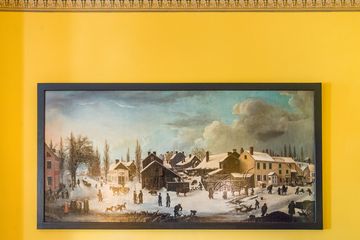

Archibald Gracie, a prosperous merchant of Scottish ancestry, had the mansion built in 1799 as a retreat from the city, which at the time did not extend above Canal Street. Paul Gunther, the director of the mansion, explained, “This was their summer home, their Hamptons.” The house stands on a spot that was used as a strategic location during the American Revolutionary War due to its position overlooking the East River. Gracie, a staunch federalist, was friends with Alexander Hamilton, who called a meeting at Gracie Mansion that culminated in the creation of what would become the New York Post.

The house remained in private hands for almost a entury until it was seized by the city in 1896 for tax evasion. The mansion then underwent several metamorphoses, serving as public restrooms, a concession stand, and the first location for the Museum of the City of New York. In 1942, urban planner Robert Moses convinced the city to use the mansion as a residence for the mayor, and Fiorello La Guardia became the first to live there during the Second World War.

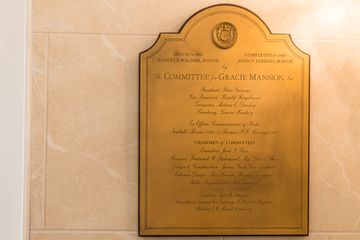

Gracie Mansion’s personal savior was former Mayor Ed Koch, who established the Gracie Mansion Conservancy in the 1980s. By that point, the house had become slightly dilapidated and, over time, much of its original components had disappeared. Koch went about restoring his home to how it might have looked during its federal beginnings. Paul explained that Koch “had the Jackie Kennedy motive,” because in the same way that she made the White House “correct” by reconstructing it to replicate its appearance during its glory days, Koch revived the residence to become what La Guardia once called “the Little White House.”

The developments at the mansion in more recent years are credited to Chirlane McCray, an activist, writer, and Mayor Bill de Blasio’s wife. It was her idea to focus on the year that the mansion was built. She hoped to draw attention to the diversity that existed in the early 1800s by displaying portraits of notable Black figures such as abolitionist Frederick Douglass and Haitian slave-turned-philanthropist Pierre Toussaint. Her work, in Paul’s words, represents “a perfect balance of respect and change” — an admirable pursuit for New York’s historic sites.