Had we not been personally escorted through the unmarked double doors that lead to Kenkeleba Gallery, Manhattan Sideways might not ever have known it was here. The only sign on the building reads Henington Hall, etched into the stone facade along with the year it was built, 1908. According to Joe Overstreet, in the 70’s the building was condemned until he and his wife, Corinne Jennings, were able to strike a deal with the city in 1978. Although 2nd Street was teeming with drug activity back then, the arrangement proved worthwhile for Overstreet, as it gave him, his wife, three children and the emerging Kenkeleba House a home in an area that eventually cleaned up its act and became one of the most important neighborhoods for the arts in New York City.

Since its founding, Kenkeleba House has flown under the radar as a not-for-profit gallery space and artist workspace. Joe and Corinne were only interested in promoting new ideas, emerging artists, experimental work, and solo shows for those deserving of the recognition. They preferred to showcase artists whose works were not typically featured in commercial galleries, focusing primarily on African American art. Joe and Corinne’s vision of Kenkeleba House - as a space for artists to grow, to showcase African American that oftentimes would have been lost, and teaching African American history through gallery shows - was only possible due to their extensive background in art as well as their immense individual efforts.

Corinne was born into a family of artists in an isolated part of Rhode Island, and until she was about twelve or thirteen, she thought “that’s what everyone did- I thought people made things.” Her father, a talented printmaker who studied under Hale Woodruff, is widely known for his black and white wood engravings and costume jewelry. The Wilmer Jennings Gallery - across the street on 2nd Street - is named for him. Jennings’ mother was a Yale graduate and painter. Corinne came to New York in the 1960’s, originally wanting to be a scenic designer. Even though she was qualified, she was turned away by the head of the scenic designer’s union with the explanation that they did not want any women or black people. She instead started to do art projects, and eventually decided to “tackle some of issues that prevented African American artists from fully developing.”

Corinne and Joe spent a lot of time speaking with artists from different parts of West Africa and the Caribbean, eventually coming upon the realization that “they needed to find a different way for people to develop, for people to have space to work, [and] to find alternative educational routes for people.” In 1978, Joe and Corinne purchased an abandoned building on second street, fixed it up, and opened up their first art exhibition in 1980. From then on, they began amassing their extensive and remarkable collection.

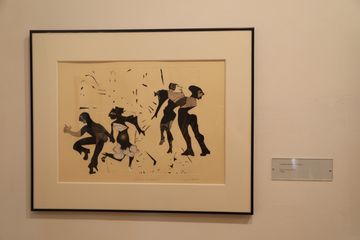

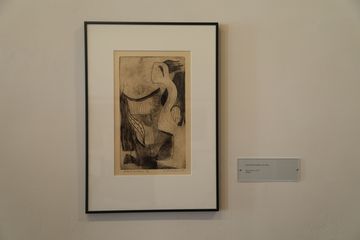

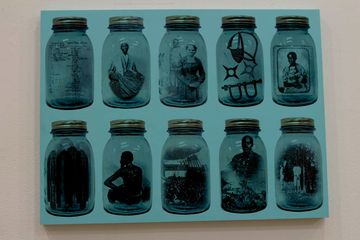

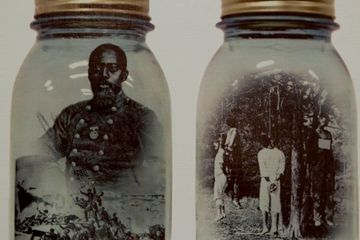

The exhibits on display in this gallery recognize the rarely explored contributions that people of African descent have made to the art world. It is here, hanging on the walls and filed away in the deepest recesses of their private collection, we were showed a portrait of Dr. John DeGrasse painted by a largely forgotten African-American artist by the name of Edward Mitchell Banister (1828-1901). Banister won a national award for his most famous painting, “Under the Oaks.” The magnificent framed picture of Dr. DeGrasse is easily worth more money than we could count, but the history lesson we received from Joe was priceless. Dr. DeGrasse was a native New Yorker and also one of the first African-Americans to receive a medical degree. He gained acceptance to the Boston Medical Society in 1854, making him the first African-American to belong to a medical association in that state. And to boot, he was also the first African-American medical officer in the U.S. Army serving as Assistant Surgeon in the Civil War. In addition, Manhattan Sideways viewed works dating back to 1773, by the late Hale Woodruff, an African-American abstract painter who lived in New York City from 1943 until his death in 1980. In addition to being an artist who aspired to express his heritage, Woodruff was also an art educator and member of the faculty at New York University.

“We are African-American, so that is what we do,” said Corinne, “but we are also interested in artists from the Lower East Side.” Corinne’s personal art collection reflects much of her parent’s amazing work, as well as that of other African-American artists, both well-known and yet undiscovered. Kenkeleba Gallery aims to teach the younger generations about African-American history. “Every nationality walks by here on a daily basis, but they have no idea who we are as a people.” Joe and Corinne were well aware of the contribution African-Americans have made to the arts that began right here in this community. Their private collection is made up of over 30,000 paintings, artifacts, art books and jazz records that tell the rich history of African-Americans in this country.