Andrew Castrucci has been bottling his own urine since 1986. The five-pound jugs began as an alternative to the single toilet all the building’s squatters had to share and were later launched off the roof like hand grenades when the police attempted to evict the residents. When the Manhattan Sideways team visited Andrew in 2017, the jugs were still defiant and airborne, dangling from the ceiling by invisible fishing lines in the gallery on the first floor of that same building. The jugs hung before a gloomy portrait of Donald J. Trump that Andrew made in 1986 and were just one installation in an entire exhibit devoted to art protesting the 45th President.

The Bullet Space gallery is a true throwback to another time in the East Village. Andrew, a well-regarded sculptor and abstract painter, runs a non-profit artist’s collaborative in his “unconventional” space. He features shows curated exclusively by residents of the building, ensuring that all exhibitions have connections to the East Village community. As Andrew explained it, “We work outside the gallery system.” The lifespan of every show is two months, in an effort to promote as many artists as possible. The responsibility of organizing the shows rotates among the artists, and each exhibition displays a variety of media and pieces from around the world. Andrew described the building as a “living workspace.”

The gallery’s title arose from an effort to take ownership of the name “bullet,” a brand of heroin so rampant in the area during the 1980s and 90s that it earned East 3rd Street the nickname “Bullet Block.” Andrew revealed how the neighborhood has changed since that time, saying: “I don’t have fifty people coming up to me everyday asking to buy coke and crack and heroine anymore.”

In 1991, the squatting artists completed a book called “Your House is Mine,” a collection of works depicting homelessness, the fight for civil rights, gentrification and other issues of the Lower East Side. The book has been showcased in the collections of twenty museums, including the Whitney, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Victoria & Albert museum in London. The book’s success, however, was eclipsed by the fallout of the reality it exposed: “I couldn’t even celebrate because I was the only one alive from the exhibition,” Andrew admitted.

Andrew and his neighbors squatted in the building until 2001, when they bought it through a non-profit for $1.00. The residents had been performing skits and putting up their artwork in the space long before the first floor became an official gallery. Although most occupants are still artists, Andrew is the sole resident who remains in the building from the initial group in 1986.

Future exhibits will include art exclusively created by children, ball-point pen works, and a show honoring the late Melvin Way, a poet who lived in the building. Bullet Space often displays art that has been rejected from more commercial venues for being too unconventional. “We’re considered off-off Broadway,” Andrew said. While speaking with him, we also learned that he teaches guerrilla art and graphic design at the School of Visual Art and has worked as a cartoon artist for the New York Times and the Daily News.

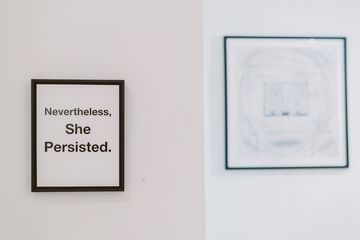

While Andrew's 2017 show, titled "Wrong Side of History," spotlighted political art, Bullet Space's exhibitions engage with a variety of topics. Andrew still carries the torch of rebellion, putting in a conscious effort to incorporate “underrepresented forms of art,” such as graffiti art, Native American art, and pieces done by women. “The show has a strong women's presence,” he told us while pointing to a pink hat found on the sidewalk during the Women’s March in NYC in January of 2017. The “interesting artifact” sat on a table below a print that read: “Nevertheless, she persisted.”

"Wrong Side of History" featured pieces from around the globe and from different time periods, touching on several themes that the current administration has been criticized for, such as xenophobia, sexism, media usage, and more. Some pieces address President Trump's more explicitly, like the giant sculpture of his head made out of horse manure that Andrew obtained from his Amish neighbors upstate. The works not only impress viewers for their visual aesthetic, but evoke queries such as "Who owns the truth?", "How are opinions shaped?", and "What happens when the viewer leaves the gallery?". The art extends beyond the physical stillness of an object to be looked at, interacting with the viewer like a cognitive jousting partner, spurring contemplation of the concepts in the gallery. “To keep your sanity, you have to respond somehow,” Andrew stated. “I believe in art having power - art can change the tide.”