Flamenco Vivo Carlota Santana fills a very important role in Manhattan: It is not only one of the few flamenco schools and companies in the city, but it also provides studios for those who tend to make a lot of noise and roughen up the floors while dancing. In 2007, Flamenco Vivo moved to its current space in a building reserved strictly for non-profits (including many other arts organizations). As Hanaah Frechette, the Managing Director, quipped, “We are a non-profit in the middle of Midtown madness.” She explained that before 2007, many flamenco groups would meet at what she called “the Mecca of flamenco” down the street. When that building was demolished, Flamenco Vivo realized that they had to step up to the plate and find another place where flamenco dancers could exuberantly stomp and stamp. “We are catering to the percussive crowd,” Hanaah said with a smile.

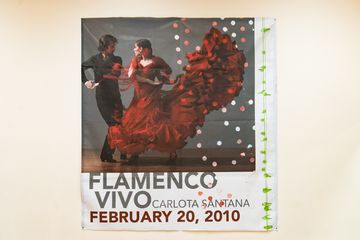

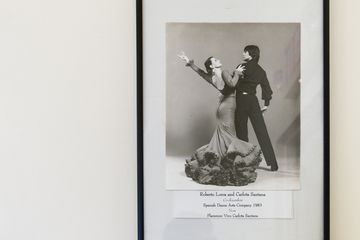

Flamenco Vivo started out solely as a dance company. It was founded in 1983 by Carlota Santana and Roberto Lorca. Though Roberto passed away in the late eighties, Carlota still acts as the Artistic Director for the company, spending most of the year in North Carolina, where she teaches at Duke University and runs a second location of Flamenco Vivo in Durham. Carlota has been honored by the Government of Spain with "La Cruz de la Orden al Merito Civil" for promoting, teaching, and performing flamenco throughout the world, and she has been called “The Keeper of Flamenco” by Dance Magazine. Hanaah proudly told us, “As a founder, she’s very involved. She’s spearheaded everything from the beginning.”

The company is composed of both local artists and guest artists from Spain, and the dancers train both in the United States and Europe. In addition to touring, they do a lot of work here in New York, thanks to the Flamenco in the Boros program, which has been offering free shows in libraries, schools, and museums. “We offer high quality performances in unusual spaces.” Hanaah went on to emphasize that the company also does arts education outreach, which includes a lot of work with English as a Second Language students, to help them feel more engaged in their communities. In addition, they have a choreographic residency each year in conjunction with a competition in Madrid. Hanaah was excited to tell us that it is her turn, this year, to travel to Madrid and present the prize to the winner. The residency allows Flamenco Vivo to support a new generation of dancers and choreographers. The studio recently started hosting a New York State Choreography Competition, hoping to foster the same growth and spirit.

Offering classes is a more recent development. Most of Flamenco Vivo’s classes are geared towards beginners, but the studios are also rented out to other programs and independent teachers. I met Juana Cala who, in addition to being an instructor for Flamenco Vivo, also holds her own classes here. I witnessed one composed of a diverse group of women. “Flamenco lends itself to all abilities,” Hanaah pointed out. She added that dancers do not need to have a specific body type in order to become a master of the form, and that participants often range in age from eighteen to seventy-five. Flamenco Vivo’s other programs reach an even broader age range: For example, Hanaah told me about the studio’s fun family-friendly holiday program, Navidad Flamenca, which explores the traditions of the Spanish-speaking world. “I love how robust and accessible our programming is,” Hanaah gushed.

The breadth and openness of Flamenco Vivo’s work echoes the art form itself. Hanaah admitted that before she came in contact with flamenco, she thought the dance form was “a complex mysterious being.” It was not until she started coming in contact with flamenco that she realized “there are lots of points of entry.” Not only does flamenco rely on many different types of artists (singers, dancer, musicians, etc.), but it also relies on many different cultures, including Sephardic Jewish, Islamic, and, of course, Spanish. Hanaah stated, “It’s an art form born of the people.”